Lenin’s Odyssey, 2020-2021

I stumbled upon the abandoned Soviet pioneer camp “Cosmonaut” in the summer of 2020, during the quarantine period when, tired of dull isolation, I decided to travel across the entire Leningrad region searching for old architectural sites. The scale of this “time-lost cosmodrome” was impressive: three-story buildings, a dining hall, an assembly hall, a covered 50-meter swimming pool. About 20 buildings and structures in total, now uninhabited and half-ruined, standing on the banks of the Oredezh River in the village of Rozhdestveno.

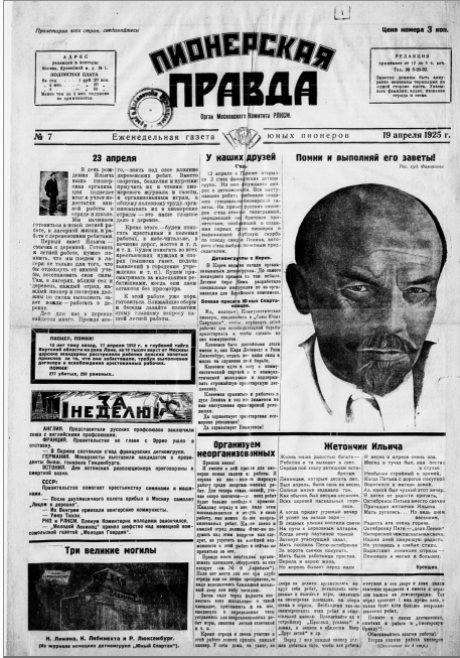

But unlike other ruins, this place evoked in me more than just a sense of lost architectural heritage. The mosaics of Lenin, cosmonauts, books about pioneer exploits — familiar symbols of late Soviet propaganda that I first encountered in school before the USSR collapsed.

I thought I had buried these images in my memory long ago, freed myself from them. But the sense of finality turned out to be an illusion. Like a radioactive element, the Soviet past doesn’t disappear immediately — it fades in fragments through a prolonged decay process. Even after many “half-life periods” — generational changes, political shifts, historical reinterpretations — the ideological mosaics, peeling portraits and wall slogans haven’t vanished: they continue to emit radiation, slowly dissipating yet still affecting visual perception, language, thought patterns, how we speak about the future and remember the past.

This drawn-out transformation of the past isn’t a linear disappearance but a cyclical presence that brings us back again to leaders' portraits on walls, to the ghostly voices of pioneers, to polished textbook imagery. Their odyssey continues — not in museums, not in tile cracks and crumbling plaster, but in the present.